Recently, the Maji Zima team attended the Menstrual Health Hygiene Summit hosted by Kenya Works. The room was filled with passionate voices from various organisations committed to addressing gender issues affecting the girl child. While the spotlight was on menstrual health, the discussions revealed something far deeper: access, in every form, is still a luxury for too many Kenyan girls.

Access is More Than Just a Product

We often talk about “access” as if it simply means availability. But at the summit, it became clear that access is layered. It’s not just about having the pads, it’s about having the information, the safe spaces, the supportive environments, and the justice systems that make menstruation manageable, dignified, and safe.

In many underserved communities, girls often lack access to a private washroom. Limited bathrooms in schools and homes mean girls skip school during their periods, or worse, risk infections and shame, trying to cope in silence. When washrooms become barriers, we’ve already failed them.

Water and Sanitation is the Missing Link

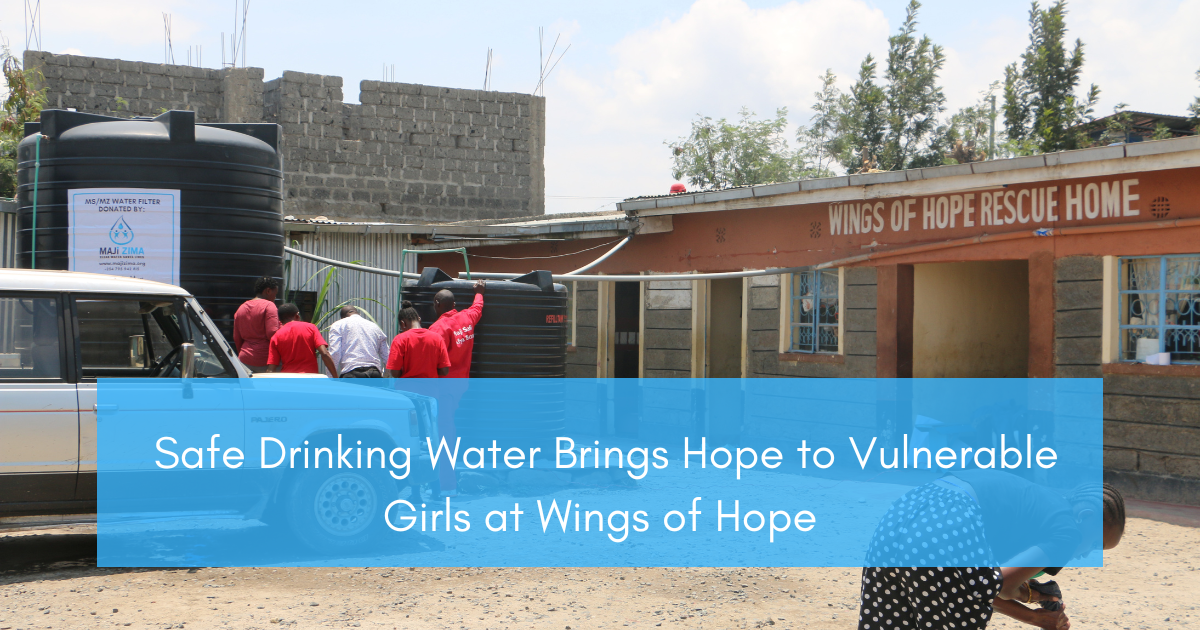

This is where Maji Zima’s role under WASH becomes critical. Without clean water, sanitary products alone are not enough. Girls need facilities where they can change safely, wash their hands, and dispose of or clean their menstrual products without fear or shame.

At the summit, we were reminded that access to water is not a privilege, but a right, especially during menstruation, when hygiene becomes even more crucial. Poor sanitation increases the risk of infections, impacts school attendance, and erodes a girl's self-esteem.

As Maji Zima, we are committed to closing this gap slowly but surely, be it through being WASH advocates or figuring out ways to provide clean water within underserved communities.

We also had the opportunity to connect with SHOFCO (Shining Hope for Communities), a large NGO with programs in water and sanitation. There’s potential for a strong partnership, and we look forward to exploring ways we can collaborate to deepen our WASH impact.

The Price of Poverty

Imagine choosing between a meal and a sanitary towel. For many families in Kenya, that’s the daily reality. In homes where even a plate of food is a stretch, menstrual hygiene products become unaffordable luxuries. In desperation, some girls are forced to exchange sex for pads or food, exposing them to further harm.

Worse still, poverty drives girls into early marriages not just because of tradition or parental negligence, but as a perceived escape from hunger and hopelessness.

When Justice Fails the Girlchild

Even worse, lawmakers debate increasing taxes on menstrual products instead of fighting to keep them free in schools. Are we putting money over safety and dignity? If so, what message are we sending to the next generation of women?

A Culture That Doesn’t Know What to Do With Empowered Women

Too often, society doesn’t know what to do with empowered women, but worse, it ignores the others entirely. Many communities still sideline women’s voices. Girls fall behind in school, not because they’re incapable, but because their needs are neglected. We need to shift the conversation. Menstrual health shouldn’t be a taboo whispered about in secret. Let’s normalise talking about periods with girls, boys, parents, and community leaders.

Education Is Not Just for the Girl

Giving a girl a pad without giving her accurate information is like handing her a key with no door. It’s crucial to educate both girls and boys, so we reduce shame and build empathy. When boys understand what periods are, we break the cycle of stigma.

Let’s teach life skills in schools, not separately, but together. And let’s also involve the parents, especially the older generation, who often raise the children and grandchildren. These conversations start at home.

Harnessing Technology for Change

Murals, digital campaigns, and charts in classrooms are not small gestures. They are visible reminders that menstruation is normal, natural, and nothing to be ashamed of.

A Call for Collective Action

The government already has the reach. Why not use barazas to educate the public about menstrual health? Community leaders can drive grassroots campaigns. NGOs can join forces in joint advocacy to push for the return of free sanitary towels in schools.

Let’s amplify the voices of girls who’ve been through it. Let them share their stories. Let’s empower not just the girls, but their parents too. Let’s include the boychild, because silence won’t save him either.

This is not just about menstruation. It’s about dignity, equality, and justice.

We must stop whispering about what should be openly discussed. We must move from shame to strength, from silence to action. The narrative must shift not just from mother to daughter, but across generations, genders, and geographies. The future of the Kenyan girl is not in the pad alone. It’s in clean water, safe spaces, accurate information, and in the power of collective change.